|

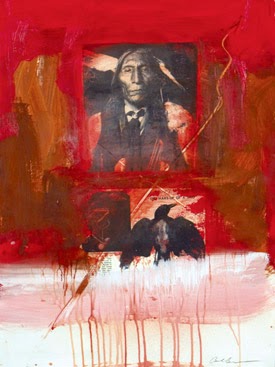

| Carl Beam, Ojibway, M'Chigeeng, 1995; Credit: Collection of the Senate of Canada |

The first landmark Aboriginal rights case is often cited as the quasi-criminal R. v. Drybones, [1970] S.C.R. 282, where the Indian Act provision that made it an offence for an Indian to be intoxicated off a reserve was found in a Northwest Territories prosecution to be inconsistent with the Canadian Bill of Rights.

Under s. 35 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the first Aboriginal rights victory was the quasi-criminal case of R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075, which affirmed Aboriginal food fishing rights in priority to other interests except conservation.

For Aboriginal treaty rights under the Charter, the quasi-criminal case of R. v. Marshall, [1999] 3 S.C.R. 456 (where I appeared as legal counsel) had huge positive ramifications for First Nations throughout the Maritimes being able to exercise fishing rights not only for food, social and ceremonial purposes, but also to earn a moderate livelihood.

Courts continue to seem to have more sympathy for Aboriginal and treaty rights claimants who are being pursued by the might of the state through prosecutions brought in reaction to their simply trying to live out traditional lives through traditional practices, as compared to harsher court views of Aboriginal claims brought in provincial, territorial and federal civil courts.

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010 is an excellent example of how reams of evidence were presented and enormous litigation costs incurred by the Gitxsan people during a civil trial that stretched through hundreds of days, only for the Supreme Court of Canada to hold that the plaintiffs hadn't quite met the test for Aboriginal title, and that a new trial should be held.

When I showed up seven years later as a negotiator at the Gitxsan table in the Comprehensive Claims process of the British Columbia Treaty Commission, where we met in Hazleton, B.C. in the "Delgamuukw Boardroom," there was still quite understandably a lot of community frustration with being told by the courts that they may have rights, but they needed yet another trial to prove them. Many of the key elders whom had testified at the first trial had by then passed on.

Civil litigation clearly has its place in advancing Aboriginal rights. The great Aboriginal title victory of Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia, [2014] 2 S.C.R. 256, where I had been involved in settlement talks that went nowhere at the trial stage almost a decade previously, clearly demonstrates that Aboriginal right s. 35 Constitution Act, 1982 success is possible in the civil court system. Indeed, Aboriginal title claims can likely only be effectively asserted in the civil rather than criminal litigation realm, because of the types of evidence and arguments that need to be presented.

Sometimes there might even be parallel civil and criminal Aboriginal and treaty rights cases proceeding in different fora. I'm currently representing two Mohawk Akwesasne young mothers in the Ontario Court of Justice in defending their rights to live out their daily lives without unreasonable state interference, including travelling around and between their reserves for work, education and social purposes without having to continually report in person to CBSA officials. They're facing quasi-criminal charges under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. The trial resumes in June 2015 in Cornwall to complete the presentation of the defence evidence, and hear Crown evidence claiming why my clients have no rights. At the same time, arguments involving different plaintiffs but some overlapping issues are proceeding in the civil court forum of the Federal Court concerning mobility restrictions on the Mohawks of Akwesasne.

That's really awesome blog because i found there lot of valuable Information. we provide chapter 7 bankruptcy attorney near Tampa Bay at affordable prices. for more info visit our website.

ReplyDeleteI would like to thank you for posting such an informative post. I got some useful knowledge from this post. Thanks for posting it. Keep it up. Bankruptcy Attorney Toledo

ReplyDelete